I am no longer reporting on the Congolese American community in New England, but not because of the lack of stories. To hear more stories about immigrant lives in America, check out Global Nation from PRI’s The World. They have a fantastic Facebook community, too.

Gallery: New American Sustainable Agriculture Project in Lewiston, Maine

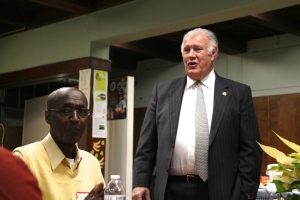

Love Your Neighbor Manchester Kicks Off

MANCHESTER, NH – Manchester mayor Ted Gatsas joined the kickoff dinner for local coalition “Love Your Neighbor – Manchester” last Wednesday night at Unitarian Universalist Church on Union Street.

“It’s a great idea to get together,” said Gatsas to the group, “in case there is a problem to rally around that problem to make sure we can fix it.”

The Manchester division of the “Love Your Neighbor” coalition was formed in September to promote unity among Manchester’s residents and create a safe, supportive, and respectful city.

The organization is a spinoff of the original “Love Your Neighbor” coalition, formed in Concord in 2012 after a string of hate crimes was committed against immigrant residents of New Hampshire’s capital city.

Concord resident Honore Murenzi organized the first Love Your Neighbor rallies in response to the graffiti messages that were found scrawled on the external walls of three separate homes in 2011 and again in 2012. The last “Love Your Neighbor” rally, held outside one of the victimized houses on Thompson Street in Concord, brought together several hundred neighbors, officials, and members of the public to voice their support of the family inside the home.

“The graffiti on the house was impactful,” said Peter Cook of Cook Associates in Hooksett, who describes himself as active and involved in diversity work throughout the state. “But what was more impactful was the reaction.”

The alleged perpetrator of the graffiti attacks, 43-year old Randall “Raynard” Stevens, was arrested in October and is currently being held on home confinement in Pembroke.

Due in large part to the “Love Your Neighbor” rallies in response to Stevens’ alleged crimes, many have seen the incident as one of unity and community building for Concord. “In the midst of danger, the community did not react in a divisive fashion. Instead, Concord identified an opportunity and responded with positive messaging and openness for learning,” wrote Concord Police Chief John Duval in a Concord Monitor editorial on October 20.

This summer, Murenzi approached the AmeriCorps VISTA Project in Manchester with the proposal to expand Concord’s “Love Your Neighbor” campaign to new cities. “He had this idea that it would spread to other cities and be a movement,” said Kerri Makinen, an AmeriCorps volunteer and one of the main organizers of the event.

“Manchester is very lucky that they have not had an incident like Concord had that was racially motivated,” said Kristen Treacy, who works for Manchester’s Department of Health and Community Policing Division. “The hope is that if we form a coalition, that will never happen.

“For me, one of the big pushes in my work is to get residents to talk to each other. If you know your neighbors, if you trust them, if you have a relationship with them, the likelihood of having a violent interaction with them significantly decreases.”

The coalition is also intended to provide support in the instance of any sort of hate crime or event of prejudice against the community. “We want to be able to respond quickly if anything happens,” said Makinen.

Members from a number of Manchester organizations attended the potluck on Wednesday, including representatives from New American Africans, Welcoming New Hampshire, and the Congolese Community of New Hampshire.

The bulk of the outreach work has fallen on the shoulders of Makinen, who was surprised at how effective word of mouth and personal invitations through email was at reaching the right people. On Monday, during her walk home, Makinen spotted the flyers she had printed up pinned to a bulletin board through a basement window.

“We all just invited people that we work with, people we know, people we see. And that was how this group came together tonight,” said Treacy.

When it was time to dig into the banquet table full of food, every chair was filled.

On January 20, Love Your Neighbor Manchester will host a breakfast open to the community in honor of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. More information about Love Your Neighbor Manchester can be found on their Facebook page.

Naturalization Ceremony at Faneuil Hall

This gallery contains 8 photos.

Snapshots from a naturalization ceremony at Faneuil Hall in Boston on December 5, 2013, where 280 immigrants from around the world were sworn in as American citizens.

Hope in a Quarter Acre: A Congolese Immigrant Finds New Home in Maine

Omasombo Katuka stands in a field filled with uprooted carrots, discarded eggplant bushes and wilting corn stalks. It’s noon in early October, but the sun already seems to have lost its strength. He frowns at a cluster of kale growing crookedly along a row, bends to pick off the fresh leaves.

The rows of kale have grown in green, crammed between drier and more decaying crops like patchwork. The corn has passed; the green pepper, too. Omasombo’s plot – a narrow, thing quarter acre slice of land – lies just 100 yards past the pebbled driveway and next to the four greenhouses where the crops are sorted and stored before sale. A little over a mile from the town line of Lewiston, the farm takes up two sides of Littlefield Road in Lisbon, Maine. The farm buildings are unassuming: a one-room farm stand, painted a rusty red; an open-air wash station, punctuated down the middle and both sides by a long, thin tables littered with wash basins; and three smaller greenhouses for harvested crops.

The rows of kale have grown in green, crammed between drier and more decaying crops like patchwork. The corn has passed; the green pepper, too. Omasombo’s plot – a narrow, thing quarter acre slice of land – lies just 100 yards past the pebbled driveway and next to the four greenhouses where the crops are sorted and stored before sale. A little over a mile from the town line of Lewiston, the farm takes up two sides of Littlefield Road in Lisbon, Maine. The farm buildings are unassuming: a one-room farm stand, painted a rusty red; an open-air wash station, punctuated down the middle and both sides by a long, thin tables littered with wash basins; and three smaller greenhouses for harvested crops.

The farm is run by the New American Sustainable Agriculture Project, a farming education program exclusively for immigrants and refugees in the Lewiston and Portland area. The year-round program couples classroom learning with practical farming to teach new Americans the physical, economic, agricultural, and financial skills they would need to grow food for income. Many of the 11-year-old project’s past participants have gone on to manage farms independently, as supplemental or the main source of income for their families.

The 30-acre farm is less than a mile from the town line of Lewiston, where Omasombo lives with his wife and eight children. It is through this farm project that Omasombo may finally have found a toe-hold, a way in to understanding his adopted country, one that had beguiled him since arriving in 2010 from a refugee camp in Tanzania.

Omasombo, a teacher in his native Democratic Republic of the Congo, escaped to neighboring Tanzania after rebel soldiers threatened to attack his family. After seven years in four separate camps, the Omasombo family – Omasombo, his wife Poya, and their eight children – was resettled in the United States, in a pocket of Nashville, Tennessee, infamously dubbed “Dodge City.”

*

Life in North Nashville was a shock. Tee Hassold, who taught Omasombo’s son David in the North Nashville school system, describes the family’s home. “It was a building with six duplexes lined up next to each other. Brick, cinderblock, hard floors, sparse furniture,” he told me over the phone. The ten Omasombos shared three beds.

The family received $800 in government benefits each month, supported only by a part time job Omasombo secured washing sheets at the local hospital from four to eight a.m. each morning. His wife Poya, with her limited English, could not secure a job.

Hassold came to Nashville for two years with Teach For America. His second grade classroom was half immigrants from Africa and half African Americans, a dynamic that he describes as difficult. All of Hassold’s students were from the same projects, a “bubble” of five blocks just north of downtown Main Street.

The school, among the lowest performing in the entire state of Tennessee, was comprised almost exclusively of African American students and immigrants that lived in the government projects. The school pitted the African American students against the African students. Blatant discrimination and name-calling was a daily occurrence for the kids in Hassold’s classroom, which were all immigrants. Hassold didn’t tolerate bullying in the classroom, but there wasn’t much he could do in the school’s cafeteria or the bus. “It got worse as they got older,” Hassold admits.

Once, the Omasombos had a bullet go through their window. Hassold doesn’t think it was a targeted thing, but a stray bullet. The eggs that were thrown at the house, however, were unmistakably aimed at the family. “It was someone else in David’s class who threw them,” Hassold says.

Hassold took an immediate liking to David, taking him out of Dodge City on the weekends to see the rest of Nashville. He got to know Omasombo’s family well, and began inviting the family to his place for dinner. Despite the discrimination that David and the other children faced at school, Hassold knows that it gave the children an opportunity to understand how life worked in their new home. The parents of immigrant children in Dodge City, Hassold explains, didn’t have that opportunity. Because of language barriers, discomfort, or fear, parents didn’t acknowledge each other, and insulated themselves from life outside their apartment.

Life in Dodge City was nothing close to Omasombo’s previous life. There was nothing familiar, nothing even recognizable. So when a friend from the refugee camp in Tanzania told them about his new life in a town called Lewiston, Maine, Omasombo was anxious to move his family north.

In the summer of 2012, Tee Hassold started a blog, “From Congo to Maine: Help the Omasombos Complete Their Journey.” With a heartfelt written plea and a three-minute video, Hassold raised $8,000 to fund the family’s trip to Maine. In a rented 15-seat passenger van, Hassold drove himself. The Omasombos, Hassold, and two friends left on July 18 for a three-day journey from Nashville to DC to Boston to Maine.

When the Omasombo family arrived in Lewiston, there were only three Congolese families in the city. That number is quickly changing – as word spreads of the low costs of living and opportunities for education, more immigrants and refugees are sure to come to the Pine Tree State.

The foreign-born population in Maine, while low compared to the national, has grown exponentially in recent years. Between the years 2000 and 2011, according to the Immigration Policy Center, the foreign-born population grew 16.5 percent, from 36,691 to 42,747. Of this foreign-born population, 11.5 percent of are from Africa. This percentage is much higher than the national average, in which only 4.1 percent of the total immigrant population in the United States is Africa.

After many hugs and a few tears, Hassold disappeared with the empty van headed back to Nashville, and Omasombo began looking for a place to live. For two weeks, Omasombo, Poya, and their eight children slept together in a spare bedroom at their friend’s house in Lewiston, but soon found a house with rent much cheaper than their government housing in Nashville. He enrolled his kids in the Lewiston public schools. It was then that his friend told him about an agriculture program for immigrants that was run out of Portland, a 40-minute drive to the south. Omasombo had experience farming at the refugee camp, and needed the income a season’s worth of crops might bring in. He signed up right away.

*

The immigrant population in Lewiston is well represented on the small farm off Route 196. Daniel Ungier, the program’s training coordinator, estimates that 80 to 90 percent of the participants are refugees, and two-thirds are Somali Bantu. The program began in 2002 in response to a large influx of Somali refugees in Lewiston, Maine’s second largest-city. The refugees overwhelmingly lived as subsistence farmers in Somalia, and the New American project helped them start small vegetable farms for the Lewiston community and direct markets. Since its founding, the program has grown to reflect the increasing diversity in Lewiston and the greater Portland area’s immigrant population. In 2009, the project teamed up with Cultivating Community, an organization that used sustainable agriculture as a tool for community development, and expanded to include training, marketing, and sales assistances for the immigrant participants.

The immigrant population in Lewiston is well represented on the small farm off Route 196. Daniel Ungier, the program’s training coordinator, estimates that 80 to 90 percent of the participants are refugees, and two-thirds are Somali Bantu. The program began in 2002 in response to a large influx of Somali refugees in Lewiston, Maine’s second largest-city. The refugees overwhelmingly lived as subsistence farmers in Somalia, and the New American project helped them start small vegetable farms for the Lewiston community and direct markets. Since its founding, the program has grown to reflect the increasing diversity in Lewiston and the greater Portland area’s immigrant population. In 2009, the project teamed up with Cultivating Community, an organization that used sustainable agriculture as a tool for community development, and expanded to include training, marketing, and sales assistances for the immigrant participants.

Even before the days got longer, back in the late winter months when the sun shone blindingly on the thick layers of ice that blanketed Lewiston, Omasombo began to attend classes provided by the New American project to learn the nuances of agriculture and farming in New England. Omasombo drove to Portland every Monday to attend classes in production and marketing, financial literacy, and farm- and market-based ESL classes. On the third weekend of April, Omasombo drove to the farm in Lisbon for the first time, and Ungier pointed to the quarter acre of land that was now his for the next six months. As a first year participant, Omasombo was provided a quarter-acre plot, seedlings, and on-site support. Other immigrants, toiling on plots around him, had graduated to the second- and third-level of the program, which incrementally give the farmer more autonomy and responsibility for handling the growing, harvesting, and selling the crops on their own.

Apart from hands-on assistance and classroom work, the project doesn’t provide much financial hand-holding. Everything that goes into the field is the participant’s own expense, says Ungier. The first year of an immigrant’s participation, they provide the seedlings, but after that farmers much manage their crops finances independently. Omasombo, despite being in his first season, has quickly become self-sufficient. “His level of independence with marketing resembles people who have been with the program much longer… but he’s still learning how the seasons work,” says Ungier.

Farming in central Africa, it turns out, is not identical to farming in New England. In the Congo, you can plant your crops twice during the eight-month season, and sell until December. In Maine, farmers must capitalize on a short, four-month season, from June to October. The hardest thing for Omasombo was learning all the new types of food, and the dates for when the food grows best. Ungier and his team, a staff of two full time farm managers and three part time assistants, teach the immigrants how to use different machines to assist in their work. They show them, crop by crop, the quality standards to watch out for. (“People don’t accept bruises,” says Ungier.) They go to the farmers markets with them, and watch the farmers interact with the customers.

*

With winter beckoning, Omasombo doesn’t come to the farm as much. Now that he has a part-time job to help support his family of ten, he can wait until the farm’s manager calls him with a request to drive out to Lisbon. Hassold, who flew out to visit with the family last fall, says that the family is much happier in Maine. “In Nashville, there was no structure for integrating them,” Hassold says. “In Maine, they have all these opportunities for integrating, but [in Nashville] there wasn’t anything like that to help them get adjusted.”

Omasombo’s children, David included, love their new schools in Lewiston. David’s third grade teacher, after reading Hassold’s blog, took an interest and visited the family often. David can relate more with his classmates – everyone plays soccer here, and they didn’t in Nashville. Omasombo likes that there is more respect shown within families and between neighbors in Maine.

Back at the farm, Omasombo leads me through his plot. Pepper, swiss chard, beans, peas, green onion, kale and row after row of the small white eggplant. Last winter, the project organized an outreach event that attracted more than a half dozen inquiries from Congolese immigrants. Although Omasombo was the only Congolese immigrant to participate this year, Ungier thinks that many more will follow his lead for the 2014 season. “Once we have someone like Omasombo, its easier for them to explain it in their own language and on their own terms – than ours,” says Ungier.

Back at the farm, Omasombo leads me through his plot. Pepper, swiss chard, beans, peas, green onion, kale and row after row of the small white eggplant. Last winter, the project organized an outreach event that attracted more than a half dozen inquiries from Congolese immigrants. Although Omasombo was the only Congolese immigrant to participate this year, Ungier thinks that many more will follow his lead for the 2014 season. “Once we have someone like Omasombo, its easier for them to explain it in their own language and on their own terms – than ours,” says Ungier.

Ungier sees potential in Omasombo – not only in his farming skills, but in his business sense. “He’s done a really phenomenal job for his first year,” says Ungier. “What’s really unique is, he’s really had his own marketing plan from the beginning.” Omasombo’s strategy has been to sell directly to the Congolese community, driving down to Portland, with its larger Congolese population, and sending his crops across the country to friends back in Nashville and even in Iowa.

Participants usually make between $1,000 and 2,000 their first year, says Ungier, although he estimates that Omasombo has made much more than this. Omasombo is especially proud of his eggplant crop, a small white eggplant that he tells me is grown in Africa. He snaps a fist-sized eggplant off the vine and holds it up for me to see.

Next month, Omasombo will start tallying up his sales. Ungier and his staff will help the immigrants keep accurate records of their income and their expenses. And in December and January, they will once again begin their production and marketing classes, preparing for another year.

Omasombo’s first priority is to learn. The more he gleans from the process, the more farming will help earn him an income in the future. “When you are in Nashville you cannot have an opportunity to learn something like that,” he says to me. The economic and financial lessons that Omasombo is getting from the program, however, extend far beyond the farm. “They can teach me how to work in America: tomorrow I can open my own business.”

SAVED! Benine Mudymba Creates a Safe Space for Young Congolese Women

Benine Mudymba was barely a year old when she arrived in the United States from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Although she has no memory of life in Africa, her parents spoke French in the house, and she grew up eating Congolese food and hearing Congolese music.

Mudymba has watched her mother, Francine, become a leader in the Congolese community north of Boston. Francine’s beauty supply store in Malden serves as an informal gathering point for women, and she spends much of her time driving new immigrants and refugees to doctors appointments and lawyers’ offices as part of her work for the Congolese Women Association of New England (CWANE).

But last year, 21-year-old Mudymba struck out on her own. Mudymba had begun to notice that women her own age were not attending the Congolese women’s association meetings and activities. “The women between the ages of 18 and 28 feel like they’re too young to be going to these meetings — they’re for the older moms,” says Mudymba.

In March of 2013, Mudymba established her own chapter of CWANE, which she named SAVED. SAVED, or Sisters After Virtue, Edification and Diligence, was created for young women to meet and discuss issues that were important to them. “I knew that I wanted to do something for women,” says Mudymba. “I wanted to do something on my own.”

Mudymba knew a lot of the daughters of CWANE members through her mother and from her volunteer work. The first SAVED meeting in March, held in a second floor employee conference room of the Stop and Shop in Lynn, attracted a dozen girls. Mudymba had attendees jot down topics they wanted to learn more about, and has based the first six meetings on that list. In May, the topic was women’s health; in June, it was being content in the different seasons. In July, it was peer pressure, and in August it was boundaries.

November’s meeting will be about finances and budgeting. Mudymba researches and prepares handouts for each meeting, and begins each gathering with a focus activity to get the girls to relax.

Mudymba keeps a meticulous blog for the group, complete with a schedule of upcoming meetings, notes and takeaways from previous meetings, and additional resources. The SAVED Facebook page is filled with encouraging updates and inspirational quotes.

Like her mother, Mudymba has become a mainstay in her community. She emphasizes the role of SAVED as a support group, but also points out that she is available for support and guidance individually. “They can come to me personally, and say ‘I have this issue.’”

In fact, Mudymba hopes to counsel women as a career. In May, she will graduate from Salem State University with a degree in sociology, and wants to work with juvenile delinquents and abused women. Although she knows that SAVED won’t be her first priority out of school, she wants to continue with the new organization. “I do want it to be bigger, I want to devote more time,” she says.

When asked where she sees SAVED in three years, Mudymba replies without hesitating.. “I would like to have a SAVED group in every state,” she says. Mudymba wants SAVED to be a support system for all young women, not just women in the Congolese community. But for now, she is just hoping for an office. “If I were to have an office, girls would feel comfortable doing one-on-one consultations,” Mudymba says.

Above all, Mudymba wants SAVED to provide a place where any young woman can go and safely share her problems, questions, and fears. She cites the importance of her older sister helping her out as a teenager, and hopes that SAVED can provide that big-sister guidance for younger women. “It’s amazing to see some of the questions they ask, because they value the other girls opinions,” Mudymba says. Already, she sees the effect that the meetings have had on the group. “It has become a sisterhood.”

Congolese Women Association of New England Celebrates 10 Years

On October 4, Julie Kabukanyi unlocked the door to a closet-sized office in Malden, Massachusetts. She settled behind a desk that takes up the majority of the tiny office. Dressed in a colorful outfit that contrasted the grey morning sky, Kabukanyi was here to discuss the apple-picking trip that the association was taking to North Andover at the end of the month. Despite a late-night shift, registered nurse Kabukanyi meets her fellow officers at the Congolese Women Association of New England’s headquarters for their weekly check in without fail.

This association was the Congolese Women Association of New England, known affectionately as CWANE (pronounced CWAH-NEE) and the meeting occurred on the eve of its 10-year anniversary as an organization. The idea for the group started back in 2003, when Kabukanyi and a half dozen of her peers noticed the problems that Congolese women were having with communication barriers and cultural issues and decided to call a meeting. Through word of mouth – news travels fast through families, neighbors, and church congregations – women came from every state in New England to gather and discuss common issues they face as Congolese women in America. “Women were very happy. We were waiting for something like this,” said Kabukanyi of that first meeting.

Since then, the Association has provided services to Congolese women throughout New England, including immigration counseling, ESL classes, job training, and cultural practice workshops. Kabukanyi, CWANE’s president, and the other two officers, Francine Mudymba and Anne Marie Wamba, work with new arrivals to navigate the legal and healthcare system.

Whereas other non-profit service organizations like the International Institute or Catholic Charities provide a set of services for a broad population of immigrants, refugees and asylees, CWANE provides similar services to a very specific group of women. Their ESL classes, held in a second floor conference room above a Stop and Shop in Lynn, are specifically for Lingala or Swahili speakers. Most importantly, the Association works to connect those who need help with those who can best provide it. “They come easily to us, because we are Congolese too. We speak their languages, and we serve as those in-between people,” said Kabukanyi.

Mudymba, who runs a beauty supplies store on Salem Street in Malden, said her store acts as a gathering point for Congolese women. “It’s like a networking place where everybody comes,” said Mudymba. “They’re coming to shop but usually they come with a problem.” When Congolese women come by the store looking for an apartment, for a doctor, or for help with their English, Mudymba always knows who to call. Many times she’ll close the store to take a woman to a lawyer or a doctor’s office, and race back to Malden to open the store by noon.

The three women are the gatekeepers to their community. With over ten years of experience, they are able to identify women’s problems and match them to the right service organization, doctor or lawyer. Kabukanyi said that the biggest issue for women is the unfamiliar role of power and confidence women are expected to hold in America. The social inferiority women are subject in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is quickly replaced by new expectations of self-assurance, a dramatic change that causes much confusion and reticence in new Congolese immigrants. “In the DRC, a woman doesn’t have a voice,” said Kabukanyi. “We have traditions, we have customs that require a woman to be like a second citizen. But when we come here, it’s different. You have to be bold, you have to be more outspoken. And we don’t have that in our culture. It’s a barrier, really.”

Wamba, who works during the week as a psychologist at Dorchester House, said there is a lot of PTSD and psychological trauma from what the women saw and experienced before coming to the US. The Democratic Republic of the Congo has experienced almost twenty years of civil unrest as rebel groups such as the Mai Mai, FDLR, and most recently the M23 perpetrate atrocities on the civilian population, causing an estimated 2.6 million internally displaced. Most Congolese that are resettled to the United States in recent years have been direct witnesses to such violence. Wamba works out of the Association’s Holden Street office on Fridays and Saturdays as a counselor to any Congolese woman who wants to talk.

Even Kabukanyi, who left the Congo when she was 30 with a bachelor’s degree in English, found the ideas of these traditional gender roles hard to shake. “I’ve been in this country for more than 20 years, but it’s still hard for me to look a man in the eye. Because a man, for me, is the authority figure,” she says.

In recent years, the women have assumed greater roles as leaders in the community. After many difficulties placing unaccompanied refugee minors in American foster homes, the Office of Refugee Resettlement began working with the Lutheran Social Services organization to place these children in families of the same culture. Both Mudymba and Wamba have become licensed foster parents, and Mudymba currently is the foster parent of two refugee children from the Congo.

Finances are tight. In the last two years, Wamba has increased the number of grants the Association applies for, although they have yet to hear any good news from the government. Unlike other service organizations, CWANE is completely volunteer-based and acts like a referral service to existing government programs. For now, they are resigned to holding their officer meetings in the tiny office space on Holden Street, although Wamba is applying for grants for a larger space. It is Kabukanyi’s goal to begin holding twice annual General Assemblies, where Congolese women from across New England can gather to discuss issues in the community.

After 10 years, the Congolese Women Association is helping not only the web of Congolese women throughout New England, but the women who run it as well. “Financially we are straining right now,” admitted Kabukanyi, but the lineup of events they planned for the fall showed no hint of austerity. There was apple picking, youth group meetings, and a Toys for Tots campaign to plan for the Christmas party. There was no talk of officially marking the anniversary of the organization, although Kabukanyi said the three of them would probably go to dinner to talk about the last ten years. “We deserve a party!” she said.

Refugees Not Yet Safe to Return to DRC, says UNHCR Advisor

After the November 4 ceasefire between the M23 rebel movement and the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, things are still not safe for refugees to return to their homes.

M23 rebels and the government have failed to agree on terms of a peace deal due to a disagreement over the wording and interpretation of the ceasefire: the DRC government claims that the M23 movement was military defeated, while M23 argues that they agreed to a ceasefire to achieve peace.

There are 40,000 internally displaced persons within the DRC and 10,000 refugees in neighboring Uganda, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ updated numbers, released on November 6.

Regional advisor to UN refugee agency UNHCR, Christophe Beau, said that armed gangs in the DRC need to put down their weapons and re-enter society before those displaced can return home, reported United Press International (UPI). “Even when a zone has been made secure people always fear to return to it because they could still be threatened by people who were in the armed groups,” Beau told IRIN Monday.

It is only when rebels have been successfully integrated into Congolese society that previously displaced persons can live in the DRC safety, said Beau.

Read more:

DRC Refugees Face Uncertain Future, UPI

Obstacles to Return in Eastern DRC, IRIN News

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre: Democratic Republic of the Congo

Arrest Made Two Years after Anti-Immigrant Graffiti Incidents in New Hampshire

In 2011, three racially-fueled acts of vandalism in Concord, New Hampshire left the community shaken. More than two years later, dogged police work exposed the criminal.

Forty-two-year-old Raymond “Raynard” Stevens, of Pembroke, New Hampshire, was arrested on October 15th. He is being held responsible for four acts of graffiti left between 2011 and 2012 in Concord. The houses that were targeted had racist and anti-immigrant messages scrawled on the homes’ walls with black marker. One of the families, a Somali family living on Perley Street, moved to Texas after the incident.

A poster was created by students for a “Love Your Neighbor” rally, held after hate-filled graffiti was left on the homes of four refugee families in Concord, New Hampshire. (Photo: Tory Starr)

After Concord police were stymied from lack of evidence, a single detective continued to look for paperwork that matched the unique handwriting on the houses. After searching through hundreds of records, the investigator found a handwritten gun permit from Stevens that matched the unique “B” found on the graffiti from 2011.

The arrest has made the entire community of Concord breathe a little easier. “It rocked our community,” said Concord police Chief John Duval of the 2011-2012 incidents, in an interview for PRI’s The World. Duval detailed how the community rallied around the targeted families after each incidence. “People came out of the woodwork to express their dissatisfaction with this type of behavior and their resolve to be active about speaking about it in a positive way.”

For the complete story on Stevens’ arrest, read Jeremy Blackman’s piece for the Concord Monitor here.

MassLive.com: “Springfield refugee task force set to meet on concerns raised by Mayor Domenic Sarno”

MassLive.com has been covering the concerns of Springfield, Massachusetts, Mayor Domenic Sarno about new refugees in his city. The latest update, reporting on the first meeting of the Refugee Task Force, was published on October 6 and can be read here.

The task force consists of representatives from the city and local refugee agencies and was formed to investigate the Mayor’s claim that the number of refugees in the city are a serious strain on Springfield’s resources.

State statistics show that a of the total 605 new refugees resettled in Western Massachusetts in fiscal year 2012, 275 were resettled in Springfield.